On Motherhood and Performance Design by Susannah Henry

In 2027, it will have been ten years since the last physical SBTD exhibition. A lot has changed in that time, for all of us.

In 2017, I travelled up to Nottingham in a fellow designer’s car, discussing the challenges of preparing our work for the exhibition alongside overlapping freelance projects. Cut to late 2025, and I am mother to three-year-old Ivor. Preparing for the next exhibition will feel radically different in terms of time and space, those familiar properties of performance design.

As a parent, I greeted the news that the 2027 SBTD National Exhibition in Coventry will include activities for children with joy. In my pre-Ivor universe, I designed many shows for young people and families but would not have predicted how becoming a mother would evolve my performance design practice. While finding my feet in early matrescence – a term coined by social anthropologist Dana Raphael as the state of ‘mother-becoming’ (Raphael 1975) – I found myself drawing on my performance design skills when creating space for my new baby at home. Designing a stage used similar skills of invention, I felt, to those used in devising spaces to share with a new small person.

I have bumped into other mothers working in performance design in the course of our work, and it has been interesting to compare notes about the way that becoming a mother has highlighted things about our world of work that we might not have noticed before. When I had the idea for this short article, I informally approached a few friends and colleagues one could define as ‘performance designers who mother’, for their thoughts about those parallel states of being. The responses that came back were rich, complicated and thoughtful.

The first friend to reply to my email – now with grown-up children – reflected on the challenges of freelance performance design gig culture, noting that she had to diversify the kinds of work she took beyond live performance, because the expectations of theatre managers often did not accommodate the need to go home and put one’s daughter to bed. My friend advocates for making ‘life as doable as possible’ around the demands of a freelance performance design career, suggesting that the flexibility created at home might counterbalance a lack of it at work.

This response was reflected by another colleague, who recalled the extremes of ‘pretending my children did not exist’ alongside rarer occasions where an inclusive theatre environment enabled her to bring her children to work. Diversifying the kinds of work taken on was also a theme here, in the name of sustaining a stable income, with added mention of the importance of keeping up to date with technology, to ensure professional currency. There must be thousands of strategies like this that underpin the reality of sole-income families with performance designer-mothers at the head of the household.

On a happier note, I also heard stories about the children of performance designers becoming intertwined with their practice in surprising and creative ways, from the brothers who excelled at photography and model-making respectively, to the toddler in the buggy accompanying his mother on a prop-sourcing mission.

It feels rare to read these kinds of stories in print. A recent example, Scene Shift: U.S. Set Designers in Conversation, edited by Maureen Weiss and Sibyl Wicksheimer, captured a portrait of American designers in the early 2020s, through a series of roundtable discussions. In the chapter Creating the Space to Work, the voices of women who are mothers and designers can be heard acknowledging the reality of designing alongside or through parenting:

Maureen Weiss: The objects are interesting, of what you actually do need around you to begin the work, because I’m usually at a loss. I’m grabbing for things – between kids, toys.

Collette Pollard: It really changed for me when I had my son because he was up so early that the late hours were just unhealthy for me… I just really trained myself to be a day person because I have a finite amount of time.

The editors of Scene Shift indicate that their book was conceived as a platform for those not previously represented in published work about performance design: people of colour, young designers and, more generally, women performing what the editors referred to as ‘our juggling act’ (p1). This is refreshing change from the familiar handbooks and monographs which tend to exclude lived experiences of parenting and the other realities that can underpin the work of the performance designer.

In the introduction to Jocelyn Herbert: A Theatre Workbook (1993) – a book we’ve probably all borrowed from libraries or have on our shelves about the inspiring 20th century British stage designer – Jocelyn indicated that for her, the journeys of motherhood and career in stage design were kept quite separate: “I finished training in 1938, but the war, getting married and having four children put an end to designing until 1956” (p15)

This twentieth-century perspective contrasts with the experience of a contemporary who has had to fully involve her child in the daily practical work of performance design, including breast-feeding him during tech. She recalled seeing her son attempting to breakdance during a rehearsal for a new musical, surrounded by the encouragement and enthusiasm of the young cast. This account brings us back to the importance of the SBTD exhibition workshops, and the value of creating space for children to engage with arts practices of all stripes – such moments are good for everyone.

My thanks to those friends who shared their experiences for this article – there is most certainly scope for further discussion. Meanwhile, I offer solidarity to members who will be preparing work for the 2027 SBTD Exhibition – Design | Stage, alongside and through mothering. Perhaps see you there with our offspring in in tow, ready to plunge into a workshop celebrating our professional practice.

References

Courtney, C. (ed.) (1993) Jocelyn Herbert: A Theatre Workbook. London: Arts Books International.

Raphael, D. (ed.) (1975) Being Female: Reproduction, Power and Change. Mouton & Co.

Weiss, M. and Wickersheimer, S (eds.) (2023) Scene Shift: U.S. Set Designers in Conversation. New York: Routledge.

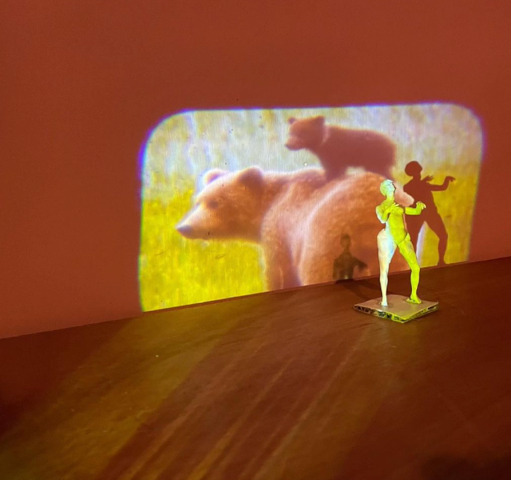

Image from cover of Maternal Ecologies: Feminist Practices of Motherhood, Land, and Creativity. Edited by Jessie Carson, Jodie Hawkes, and Pete Phillips